Thermal vs Night Vision Cameras

- Admin

- May 30, 2016

- 2 min read

Let’s start with a little background. Our eyes see reflected light. Daylight cameras, night vision devices, and the human eye all work on the same basic principle: visible light energy hits something and bounces off it, a detector then receives it and turns it into an image.

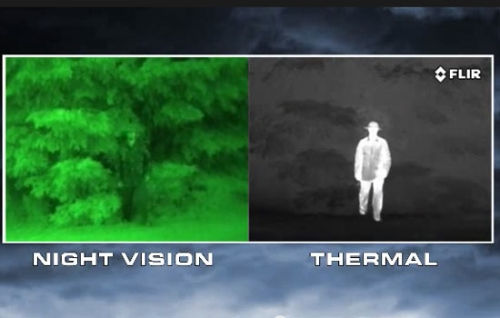

Whether an eyeball, or in a camera, these detectors must receive enough light or they can’t make an image. Obviously, there isn’t any sunlight to bounce off anything at night, so they’re limited to the light provided by starlight, moonlight and artificial lights. If there isn’t enough, they won’t do much to help you see. Night Vision Devices - Those greenish pictures we see in the movies and on TV come from night vision goggles (NVGs) or other devices that use the same core technologies. NVGs take in small amounts of visible light, magnify it greatly, and project that on a display. Cameras made from NVG technology have the same limitations as the naked eye: if there isn’t enough visible light available, they can’t see well. The imaging performance of anything that relies on reflected light is limited by the amount and strength of the light being reflected. NVG and other lowlight cameras are not very useful during twilight hours, when there is too much light for them to work effectively, but not enough light for you to see with the naked eye.

Thermal imagers are altogether different. In fact, we call them “cameras” but they are really sensors. To understand how they work, the first thing you have to do is forget everything you thought you knew about how cameras make pictures. Thermal cameras detect more than just heat though; they detect tiny differences in heat – as small as 0.01°C – and display them as shades of grey in black and white TV video. This can be a tricky idea to get across, and many people just don’t understand the concept, so we’ll spend a little time explaining it. Everything we encounter in our day-to-day lives gives off thermal energy, even ice. The hotter something is the more thermal energy it emits. This emitted thermal energy is called a “heat signature.” When two objects next to one another have even subtly different heat signatures, they show up quite clearly to a FLIR regardless of lighting conditions. Thermal energy comes from a combination of sources, depending on what you are viewing at the time. Some things – warm-blooded animals (including people!), engines, and machinery, for example – create their own heat, either biologically or mechanically. Other things – land, rocks, buoys, vegetation – absorb heat from the sun during the day and radiate it off during the night. Because different materials absorb and radiate thermal energy at different rates, an area that we think of as being one temperature is actually a mosaic of subtly different temperatures. This is why a log that’s been in the water for days on end will appear to be a different temperature than the water, and is therefore visible to a thermal imager.

Reference: http://www.flir.com/cvs/americas/en/view/?id=30052